GitOops! Attacking and defending CI/CD pipelines

GitOops! Attacking and defending CI/CD pipelines.

As part of our ongoing quest to improve the status quo of CI/CD security, we present GitOops: a tool to map CI/CD attack paths in a GitHub organization.

Lateral movement and privilege escalation via CI/CD pipelines is old news for those in the know. Despite this, the security community has so far invested little effort into producing literature and tooling to improve the situation.

We will start by motivating our work by presenting an overview of the issues we are trying to spot at scale. We will then gloss over GitOops’ inner-workings before demonstrating usage with some sample scenarios.

Note

I originally published this on the ovotech blog. It is reproduced here as a mirror.

GitOops got picked up by tl;dr sec, CloudSecList and DevOps Weekly. Thanks for the mentions!

Introduction

With the proliferation of CI/CD integrations and dynamic checks in Version Control System providers, users can directly and indirectly run code in a variety of contexts by pushing changes to repositories. The most common example is running code in a CI/CD runner by triggering software test suits from a feature branch when opening a pull request or pushing to a feature branch.

Combined with lax access controls to repositories and their branches, this can offer easy paths for lateral movement and privilege escalation within an organization.

Here are a some common scenarios:

-

The lack of production branch protections on a repository with a production continuous deployment pipeline could allow anyone with write access to the repository to deploy malicious changes to production.

-

The lack of branch-based access controls for secrets in CI/CD systems like CircleCI and, historically, GitHub Actions, means that an untrusted (unreviewed) feature branch may have access to production secrets when running a build in a pull request context.

-

Running a Terraform production plan on an untrusted (unreviewed) feature branch may give untrusted infrastructure code and Terraform providers access to production and production secrets.

-

An excessive number of administrators on a critical repository can increase the chances of branch protections being disabled to enable an attack via CI/CD pipelines.

As organizations grow to have thousands of repositories, hundreds of users and teams, use dozens of CI tools, and empower teams with autonomy, it is unreasonable to expect security teams to manually investigate and keep tabs on these attack paths.

Graph DBs aren’t just for hipsters

Graph databases are cool and trendy, but they can also be useful.

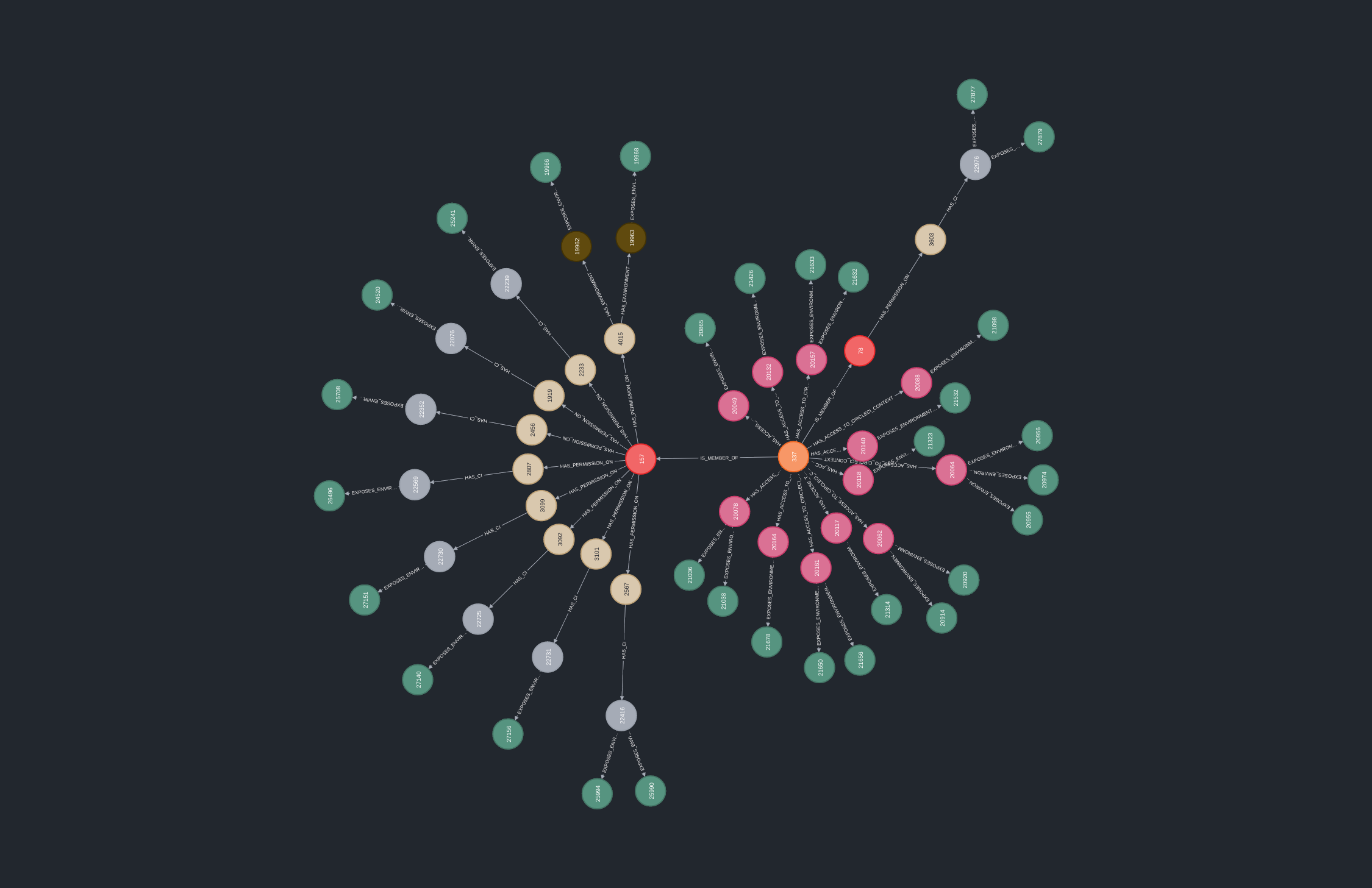

If we abstract away the details from the scenarios above, what we’re really looking for are relationships between GitHub:

- users

- teams

- repositories

and CI/CD:

- jobs (i.e.

deploy prodortf-plan-prod) - environment variables (often secrets)

The relationships we are looking for are of moderate depth and can take several different forms.

An organization may use different CI/CD systems. We mostly use CircleCI, GitHub Actions and AWS CodeBuild, with a dash of Jenkins laying around for good ol’ legacy reasons. Most CI/CD systems support user-defined environment variables, but with different twists. For example:

- CircleCI has Contexts (which are a way of reusing a bundle of environment variables across projects) but also supports a way of directly attaching environment variables to specific Projects (which have a one-to-one mapping with GitHub repositories)

- GitHub Actions also supports attaching environment variables directly to repositories, but it also has a notion of Environment (essentially, environment variables directly attached to a repository, but with optional branch protection rules) and organization environment variables (available to all repositories in an organization)

These approaches are quite different. Wouldn’t it be great if we could search for all paths between a user and a secret without having to worry about which system(s) we’re targetting?

This sounds like a good case for a graph database. It’s much more fun to write:

MATCH p=(:User{login:"alice"})-[*..5]->(:EnvironmentVariable)

RETURN p

than to try to translate all possible paths into an SQL statement.

We opted to work with Neo4j and the Cypher query language; the Community edition is free, easy to use and popular. The folks at Neo4j have also open-sourced Cypher and some other graph databases have started supporting the Bolt binary protocol.

What do we ingest?

Now that we have justified the use of a hipster’s DB, what do we store exactly? We’ll gloss over this here; you’re welcome to check the code and the schema for the details.

Access Controls

We want to know:

- Relationships between users and teams within an organization.

- Repositories that users/teams can access. We’re particularly interested in repositories a user/team can open a pull request against or push to some branches (

writeaccess in GitHub) or have admin access on (allowing them to disable branch protections to abuse a production deployment pipeline triggered on a merge to the main branch, for example). - Repositories that have branch protections enabled.

CI/CD Configurations

We want to know which repositories have CI/CD configurations:

- We ingest CI/CD configuration files for popular CI/CD systems.

- For CircleCI we can query the API to figure out which repositories have a project configured.

Events

We want to know which repositories trigger jobs on pushes, pull requests and merges to the main branch. There’s a couple of ways we can get this information:

- Repository webhook configurations can tell us which repository events trigger a webhook against specific CI/CD systems.

- Status checks can tell us a lot of about which kind of jobs are run on pull requests through their name.

Secrets

For the pièce de résistance, we want to know where all the secrets are:

- For GitHub Actions and CircleCI we directly query the APIs to retrieve environment variable names. For CircleCI we can even get the value of the last four characters of an environment variable!

- For other CI/CD systems, we can extract environment variables from the configuration files if they are explicitly mentioned by regex-matching upper camel case strings. We can also look for strings that imply the presence of interesting secrets in the pipeline (e.g.

aws,terraformetc.)

Examples

Now that we’ve ingested relevant data from our GitHub organization and CI/CD systems, we can start mapping some attack paths. We’ll only cover a sample here, you can find more examples in the docs.

Finding all secrets a user can access

This query will return paths between a user and potential secrets, via several means:

- CircleCI

- “All members” contexts (available to anyone in the organization)

- team-restricted contexts (you guessed it, restricted to the user’s teams)

- repository projects (available to anyone with

writeaccess to a repository)

- GitHub Actions

- repository (available to anyone with

writeaccess to a repository) - environment (may be restricted to pushes to specific branches)

- organization (available to anyone in the organization)

- repository (available to anyone with

MATCH p=(:User{login:"alice"})-[*..5]->(:EnvironmentVariable)

RETURN p

If we want support for other CI/CD systems, we could try the query below which will look for mentions of environment variables and certain keywords in configuration files:

MATCH p=(:User{login:"alice"})-[*..2]->(r:Repository)-[HAS_CI_CONFIGURATION]->(f:File)

WHERE any(x IN f.env WHERE x =~ ".*(AUTH|SECRET|TOKEN|PASS|PWD|CRED|KEY|PRD|PROD).*")

OR any(x IN f.tags WHERE x IN ["aws", "gcp", "terraform"])

RETURN r

Finding GitHub Actions secrets without branch protections

GitHub Actions has supported branch protections for secrets since December 2020, through a notion of “environment”. Using this feature is optional.

To find GitHub Actions environment variables that are not in environments (and therefor accessible to anyone who can open a pull request), we can search for direct relationships between a repository and environment variables:

MATCH p=(:Repository)-->(:EnvironmentVariable)

RETURN p

Environments also needn’t enforce any branch protections. We can look for environment variables that can be exfiltrated from any environment through a pull request:

MATCH p=(:Repository)-->(e:Environment)-->(:EnvironmentVariable)

WHERE e.protectedBranches = false

RETURN p

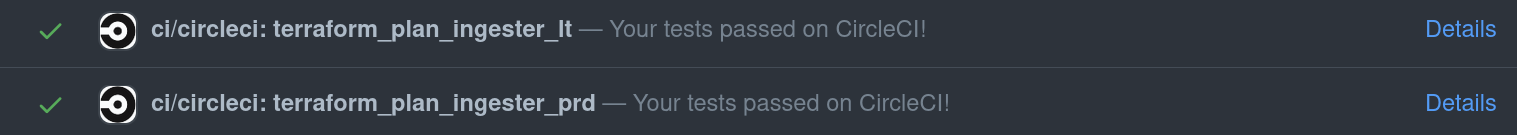

Attackable Terraform plans

Production Terraform plans on unreviewed code are a bad idea. We attempt to find these by looking at the context values on pull requests’ status checks, to get maximum coverage and account for CI/CD systems that may be configured server-side (e.g. AWS CodeBuild). The funky regex in this query means “things that contain terraform (or tf) and prod (or prd, and as long as it’s not preceeded by non):

MATCH (r:Repository)-[:HAS_STATUS_CHECK{pullRequest:TRUE}]->(s:StatusCheck)

WHERE s.context =~ "(?=.*(tf|terraform))(?=.*(?<!non)pro?d).*"

RETURN r.name

Pivoting through GitHub bots or: how I learned to stop worrying and love CircleCI

This author has yet to witness a GitHub organization of a respectable size that did not make use of one or more GitHub “bot” user accounts. Personal Access Tokens (PATs) for these user accounts also have a sneaky habit of finding their way into CI/CD systems.

What’s more, several GitHub SDKs misleadingly give the impression that you need to provide a username when using a PAT (in reality any string will do). This has the interesting side effect of leading to GITHUB_USERNAME environment variables often being found next to GITHUB_TOKEN ones.

To throw a cherry on top, CircleCI allows us to retrieve the last four characters of environment variables through their API.

I’m sure you see where this is going: if we’re lucky we can run a query to predict the access an attacker would obtain by pivoting through GITHUB_TOKEN environment variables:

MATCH (u:User{login:"alice"})-[*..5]->(v:EnvironmentVariable)

WHERE v.name =~ ".*GITHUB.*USER.*"

WITH DISTINCT(v.truncatedValue) as truncVal

MATCH p=(u:User)-[*..5]->(:EnvironmentVariable)

WHERE u.login =~ "^.*" + truncVal + "$"

RETURN p

If we’re not so lucky, we can always extract the GITHUB_TOKEN through a push or a pull request and hit the /user GitHub API endpoint to retrieve the authenticated user’s login.

What’s next?

GitOops is currently designed for one-off mappings from a security engineer’s laptop. In the future, we would like to move towards a form of continuous monitoring of an organization’s GitHub security posture. Details will be fleshed out as we move along, but this may look something like:

- run a GitOops ingestion job on a continuous basis

- remove old nodes and relationships from the database (we’ve anticipated this requirement with the

-sessionflag) - monitor events and trigger alerts when a new relationship matches a known bad pattern

We would also love to formally support additional CI/CD systems and VCS providers. If you want to contribute we’d be super interested!

You can hit up the author on Twitter @alxk7i and check out GitOops on GitHub.